The Molesworth is delighted to present an exhibition of recent paintings by Gabhann Dunne.

We're publishing a hardback catalogue to accompany the show. The introductory text by Dr Yvonne Scott can be read below.

EIGHT BILLION MYSTICS

by Dr Yvonne Scott

The titles of Gabhann Dunne’s shows are never accidental; they always have a particular relevance to the body of work on display. In this case, the ‘eight billion’ alludes to the estimated current human population of Earth. The term ‘mystic’, however, initially seems contradictory suggesting, as it does, transcendent, super-human insight. Mystics, surely, are rare individuals with a capacity for shamanic perception – high priests who commune with the spirit world, translating an obscure magic for the ordinary, the average, the human, who in turn accept the wisdom of the intercessors with wonderment and awe? Dunne’s title suggests, however, that such capacities, rather than the rare gift of the chosen few, are much more universal. As he explained in a recent communication with the author: “everyone has the potential to be a mystic”. In his interpretation, ‘mystic’ is adopted less in terms of establishment religiosity, but rather relates to the non-human world, as he suggests for example, “a sensation of sublime transportation through an empathy with a bird or a tree or ecosystem”. Mysticism for Dunne embodies a capacity to relate to environmental phenomena in a way that dissolves the traditional ‘nature versus culture’ dichotomy, so that humanity is recognised as a part of, rather than distinct from, nature.

Gabhann Dunne’s current show builds on his practice, comprising a range of works that are triggered by the artist’s curiosity and imagination. He reads widely, from science to poetry, excited by perspectives and seeking answers to his many questions. As an artist, Dunne can take advantage not only of the opportunity to probe the potential of ideas, but to translate convincing scraps of substance towards the materialised vision of his paintings. Radio-collared lynx, Beara Peninsula for example considers, from the fragmentary archaeological remains of animal bones, that perhaps lynx were once commonplace in Ireland before their disappearance, a hypothesis reimagined for the current electronic age.

Dunne contemplates the history of migratory patterns of flora and fauna, how analysis and discoveries have explored the circumstances and histories: of the limited incidence of Irish fleabane, of the means of introduction of rabbits and hares, of the demise of the Donegal wolf, of the recovered provenance of the native Scots pine, the subject of a remarkable installation by the artist. He observes too how relatively recent migrations of creatures have become normalised through familiarity, citing the example of Eurasian collared doves that arrived in Ireland just over sixty years ago. Unusually in artistic representations, he anticipates the future. Morrigan with ring-necked parakeets, depicts the artist’s daughter flanked by two birds that are included, not as exotic pets as might initially be assumed, but as creatures that were first observed in the wild in Ireland less than twenty-five years ago and that are destined to become commonplace within his daughter’s lifetime.

A distinctive aspect of Dunne’s practice is the arrangement of the components of a show. Conceived as an installation, in that all the works included relate to a comprehensive idea as opposed to comprising a series of entirely independent artworks, the paintings are of varying sizes and are shown in a format that reflects how Dunne identifies inter-relationships in the real world, as opposed to how artworks are traditionally presented according to some kind of aesthetically determined scheme. The Burren Pines installation for example comprises a series of individual paintings of trees, all of which bear the similarities of a species, while each reflects it owns idiosyncratic growth habit. These paintings are arranged to suggest a copse or forest, and while a perspectival artistic view of such a grouping might suggest the illusion of space and the obscuring of some trees behind others, Dunne’s approach gives each of the organisms its own space and identity within the group. Similarly, in the current show, each of the works has its own presence while belonging at the same time to a wider population of existence.

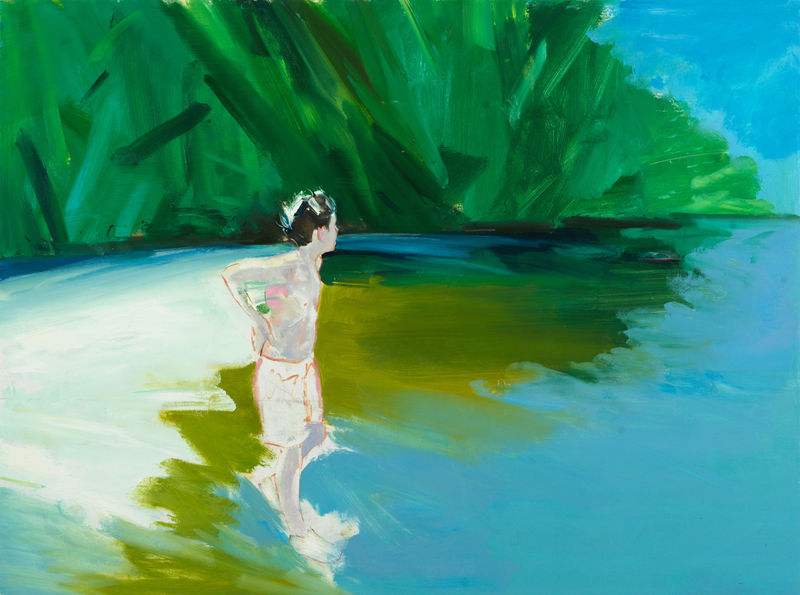

The artist has commented on how geographic and environmental factors impact on the construction of identity, and that while geography may remain fixed, the environment is unlikely to do so in the era of climate change. The re-wetting of Abbeyleix references contemporary efforts at habitat restoration, to recover a landscape under threat. The artist explores the place of water in the archaeology of Ireland, including the inundation by sea of formerly dry land, as for example in Drowned forest, Ballycotton, as well as in its frozen forms of snow and ice, reflected in images like Devonian snow. Another painting, Liffey wolf, is an imaginative reconstruction that features the artist’s son as he glances along the river that must have been crossed by a wolf at some time before the animal was wiped out in Ireland. The relationship of water with the migratory activity of creatures, whether local or more distant, is alluded to in paintings like Irish hares don’t swim, or American migrants. The scope of the artist to creatively imagine through allusion is projected in images of birds in the process of movement through surroundings that could be air or water, as in Submerged swallow. Dunne’s familiarity with a range of species emerges in his easy reference to the ring ouzel or the wheatear, each of which are subjects of his paintings.

The interconnections may in some cases, be convoluted, reflecting the duration and complexity of processes in reality. Thus while trees feature in various images, Dunne has commented in discussions on the introduction of the arbutus in the south of Ireland, a tree noted for its capacity to produce charcoal, necessary for the smelting of the products of mining. While Saint Gobnait is commonly associated with bees, she has also been identified as the patron saint of mining and blacksmithing, through the association of her name with the Irish word for a smith, and thus the relevance of the inclusion of a painting of a female figure, entitled Gobnait, who is relevant as one of the eight billion mystics.

The interconnections of time also reflect Dunne’s range of interest from depictions of the instantaneous and dynamic, to the extended histories of eons before human existence. While humanity tends to understand time within the limited framework of life expectancy, Dunne conflates the distant past with the present, identifying current matter (like a plastic garden chair) with the pre-historical origins of its component matter, in the Devonian era, hundreds of millions of years ago.

Dunne refers to the ‘conflict between gesture and content’, that is, between his fascination with the practice of painting, and imaginative reconstructions with the curiosity that leads him towards a plethora of academic resources. Dunne’s capacity as an artist is related also to his scientific curiosity when he explains about his practice of blending colours to achieve the particular tone he seeks, or the distinctive array of paint textures, how they work on the substrate and the potential for combination.

The most exciting artists are those with alternative ideas and perspectives, along with the capacity to articulate them through their technical ability. Gabhann Dunne’s explorations reveal an insatiable curiosity for both knowledge and creative reconstruction, combined with his appetite to experiment and discover convincing resolutions to recreate the possibilities of technique and display.

Dr Yvonne Scott is Fellow Emerita and former Associate Professor in Art History, Trinity College Dublin.